Mobility and Net Zero: How accessibility can contribute positively to transport carbon targets

- Post Date

- 04 March 2023

- Read Time

- 8 minutes

For too many years we’ve heard that same rhetoric echoing that climate change cannot be ignored and that action cannot be delayed. However, the gap between these words and action has not shown the same urgency. It’s only very recently that we seem to have acknowledged the gravity of the issue and are taking some steps to avoid an existential threat to humanity. Though, in some circumstances, it’s too little, too late. This is extremely evident in Alaska where rising sea levels, increasing erosion rates, thawing permafrost, diminishing sea ice, and increased food security issues are leading to village-wide relocations.

Climate has affected 85% of these communities and as a company, we are now seeking to relocate them. We must all now ashamedly realise the costs they have incurred from inaction – their indigenous culture is being eroded as quickly as their coastlines.

While Alaska might seem a far cry from the effects we’re seeing in the UK, the entire planet is in a similar spiral and the time for us to feel similar effects is fast approaching.

We can’t live and make decisions in the way we have been, and we’ve certainly passed the point where making small changes will make the necessary difference. Reversing these effects is no longer on the table, but if we are serious about minimising our effect on the planet, tinkering around the edges is not an option.

Transport could be the biggest win for climate in the UK

Surface transport in the UK represents a staggering 25% of greenhouse gas emissions. To be a climate-neutral continent by 2050, transport must achieve a 90% reduction in transport-related greenhouse emissions. Through the RTPI Net Zero Transport: Place Based Solutions study we explored the interventions required to achieve this reduction.

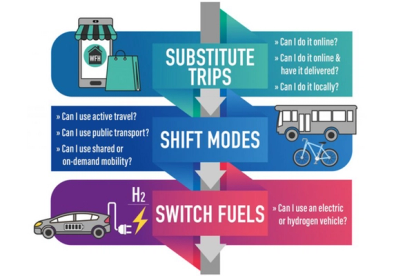

Fundamentally, two factors influence carbon emission from transport: the distance travelled, and the amount of carbon emitted per unit distance.

The easiest win for this is to avoid these trips by adopting a local living approach that focuses on accessibility to services and facilities rather than transport. Switching fuels and the move to EVs is of course necessary, but it isn’t a magic bullet and regardless, it won’t come soon enough to meet critical targets. If we rely on EVs only, we will fail.

We must put the targets into perspective. Based on steamy assumptions about improving local living by 20%, population growth of 10%, sustainable mode shift of 20%, the expected trend in electric vehicles of 80% by 2050, and a substantial uptake of sustainable electricity generation, we still won’t meet the 2050 transport target.

However, for the first time in history, the policies exist, the evidence exists, and the global will exists. We have the opportunity to embrace this and practice real-life approaches to transport and mobility that are bold and ambitious.

Build it and they will come

We can start with our approach to traffic. In increasingly congested networks the volume of traffic is more a function of the available road space, rather than the volume of development or growth. It’s known as the fundamental law of transport – build it and they will come.

That is one of the less surprising conclusions from the EU study, CREATE, which looked at how trends and interventions reduced traffic and congestion in five European cities, London, Vienna, Paris, Berlin, and Copenhagen. In all five cities involved in the CREATE project, road space for cars has gradually reduced and car trips have been falling, whilst population and total trips have been increasing. These findings were used to inform policy in other developing cities in Europe where congestion was increasing. The cities aim to move from Stage 1 (car dominance) and Stage 2 (car and public transport dominance) cities to Stage 3 and Stage 4 cities, where placemaking is of greatest importance.

This research led to the now adopted practice of the Vision & Validate approach to transport as opposed to the old hat Predict & Provide, where we would forecast a demand and design to accommodate the convenience of the car commuter.

Vision & Validate allows you to start by setting a vision of what you want to achieve and then design accordingly. No longer must we design to accommodate a theoretical demand – a necessity if we stand any chance of maximising local living and sustainable modal shift.

Mobility trends

Transport planning has become as much social science as maths and modelling. The EU project MIND-SETS studied social attitudes across Europe, predominantly looking at generational trends. It found a marked difference in attitudes to accessibility between these generations. The younger generations were far less interested in owning and using cars with both license take-up and car trip rates decreasing, unlike older generations where cars are status symbols and a necessity for life, and rates continued increasing.

This trend was common across Europe, and we’re now reaching a pertinent time where there is a correlation between these younger generations reaching a political and professional age, and European policies converging towards climate, health, and placemaking.

COVID has meant an acceleration in trends towards increased local living and working, and people have found lasting ways to minimise their inconvenience. In the UK, we’ve seen trip rates come down about 14%, although unfortunately this is being largely negated by population growth.

Nationally, traffic in the old-fashioned commuter peak periods is down about 15% whereas mid-week traffic is only down by about 5%. People now have the flexibility to choose to travel at times of least inconvenience.

LGV and HGV movement are up about 5% – 10% but these are largely outside of the traditional commuter peaks, consistent with the SAM Framework’s tier of substituting trips.

The congestion index profile across London has both reduced and flattened, moving away from those old commuter peaks.

A large part of this shift is due to an increase in work flexibility. On average nationally, at any single point in time, about 25% of people are working from home, or a third place, compared with about 15% pre-COVID. Encouragingly, in some London Boroughs it’s as high as 40%.

Reimagining our streets

The EU MORE study, including London, Malmo, Lisbon, Constanta, and Budapest has been experimenting and stress testing urban street design and space reallocation. It looked at concepts that encourage street activity, flexible use of kerb space, and dynamic reallocation of roadspace. It also investigated the need for new policies and regulations, and analysed the role of technology.

Wrapped up into a new handbook, Better Streets for Better Cities, the results include an appraisal tool, a simulation tool, and a stakeholder engagement tool. To successfully implement local living and sustainable town centre movement, mobility hubs will be vital. Primary mobility hubs fulfil a community role as well as a mobility role, with community concierge, café, micromobility hire and microconsolidation. Secondary and tertiary mobility hubs integrate the community or town centre with these primary hubs and the concierge team.

Tertiary mobility hubs can be seen throughout European cities, for instance in Bremen where basic mobility facilities are being installed every 300 metres in the city centre area. Germany is paving the way for mobility innovation in many senses, having also combined Berlin’s entire public transport and sharing service in one real-time app, Jelbi. It brings together 12 different mobility services, integrating them into one Mobility as a Service (MaaS) package.

Barcelona has been using masterplanning to affect mobility through Superblocks trials for some time now. They are largely traffic-free blocks, where all major services, roads, public transport, and deliveries are confined to the edge of the block and the centre is restricted, providing an exemplary public realm. This is their vision for the city.

It’s time to be bold

Despite the fact we have the evidence and policies to support approaches similar to these European cities, we still encounter the ‘what if’ roadblock. To encourage change and to combat this obstructive mentality, we often include a ‘Monitor and Manage’ package when working on new developments. It allows us to reflect on which sustainable measures work best in certain circumstances. Funded by a Flexible Transport Fund, those successful elements can be accentuated, and others could be abandoned or modified. It’s a sensible method of allowing for change over time, benefitting from observed effect, and maximising the contribution of new development or growth to the three key policy strands of climate, health, and economy.

As professionals working in the largest emitting sector, we have the opportunity to provide the greatest contribution to achieving the net zero target.

It’s time for us all as policymakers, decision-makers, and designers to be bold.

We can’t be afraid of trialling new ideas.

We can’t live in fear of ‘what if’.

Recent posts

-

-

-

Navigating the evolving landscape of corporate sustainability and communications in the US

by Chynna Pickens

View post