Key highlights from the IPCC AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis

- Post Date

- 02 February 2023

- Read Time

- 7 minutes

This blog post is the first in a four part series unpacking the key pieces of information from the IPCC AR6 reports. Part two - Key highlights from the IPCC Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability report. Part three - How to keep global warming to within 'safe levels'.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces a set of major reports every seven years summarising the latest climate science and its implications for human society. It is currently in its sixth assessment report cycle (AR6).

In August 2021, the IPCC released the first report in the series, AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. For many familiar with the topic, this report did not provide many headline surprises, although it did provide an update to its climate scenario modelling and included the outputs from a new set of climate models (CMIP6). This means more advanced and up to date forward-looking physical climate risk data is available for scenario analysis and planning.

In this blog post we explore the key highlights from the report, the emissions pathway we are tracking, the topic of abrupt climate tipping points and the logic of a 1.5°C versus 2°C target.

Key highlights from the report:

- In almost all emissions scenarios, global warming is expected to reach 1.5°C “in the early 2030s.”

- In the high emissions scenario SSP5-8.5, the world will reach 1.5°C half way through 2027.

- Future abrupt changes and “tipping points”, such as Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse and changes to the Gulf Stream, “cannot be ruled out.”

Key analysis points:

- The IPCC is warning that we are well above the emissions pathway required to achieve the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to “well below 2 degrees.”

- The IPCC acknowledges the uncertainty surrounding tipping points. However, what is clear is that every tonne of GHG we avoid putting into the atmosphere could be the difference between triggering tipping points and maintaining relative normality.

- We will soon be departing from the relatively stable temperature band in which human society has so far developed and thrived.

Climate Targets

The goal of the Paris agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. The IPCC found that the world has warmed by an average of 1.1°C and in all emissions scenarios, global warming is expected to reach 1.5°C “in the early 2030s.”

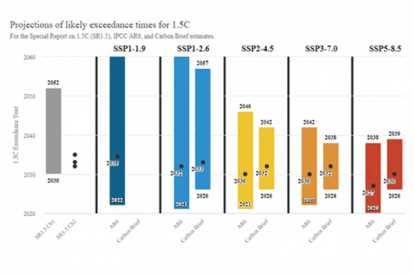

Projections of likely exceedance times for 1.5C

Much of the warming which will occur up until 2050 is already ‘locked into’ the system due to past emissions that are yet to translate into temperature rises. This is why all of the warming pathways look very similar for the next 10 years or so. In effect, we are seeking to influence how much warmer the world gets beyond the 2030s and what we do this decade will be key.

The problem with a 1.5°C or 2°C target

It is easy to assume that so long as we meet the 2°C target we will have mitigated the worst impacts of climate change, but unfortunately the reality is not so simple. Indeed, 1.5°C or 2°C have always been political aspirations rather than science-based. Global warming is ultimately influenced by concentrations of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere and these are already at unprecedented levels.

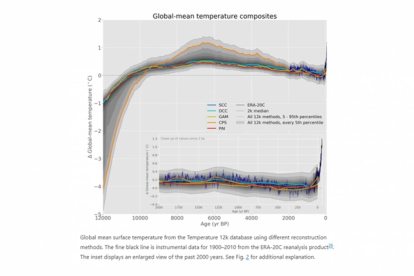

For hundreds of thousands of years, the planet has been cycling between cold and hot periods, known as glacials (i.e., ice ages) and interglacials. Each cycle usually takes place over ~100,000 years and in these cycles global average temperatures during interglacials tend to be about 6°C warmer than the cold glacials.

The most recent period of human civilizational development has occurred during the Holocene, a warm period (interglacial) that started about 12,000 years ago after the end of the last ice age. The Holocene has been a period of relative climate stability, with temperatures close to or slightly above pre-industrial levels since 7,000 years ago.

However, since industrialisation, global temperatures have increased and are now higher than at any time since the last interglacial, over 100,000 years ago. The rate of recent temperature change is unprecedented. We will soon (if we are not already) be departing from conditions under which human civilisation developed and thrived.

Global-mean temperature composites

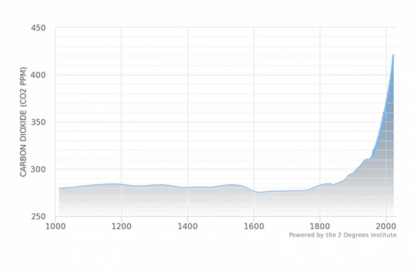

CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere are a key driver for global warming due to the greenhouse effect. CO2 concentration in the atmosphere has not exceeded 300ppm for at least 800,000 years and it currently stands at 417ppm.

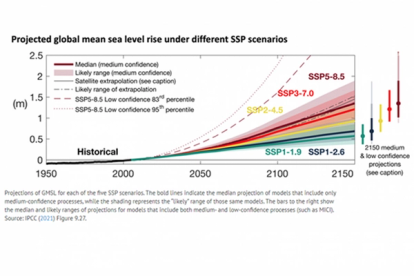

Since 1901, global mean sea level has risen by about 0.20 m and it continues to rise at an “accelerating” rate. The report states, with high confidence, that the rate of sea-level rise in the 20th century was faster than during any other century in the last three millennia and that this rate of rise has increased since the 1960s.

Projected global mean sea level rise under different SSP scenarios

Climate scientists are telling us that there is a danger that climate tipping points will be breached. However, there is a low level of certainty as to if and when that may occur. What we do know for sure is that for every extra tonne of greenhouse gas emissions released into the atmosphere, the likelihood increases. Surely it would, therefore, make far more sense to have a target to reduce emissions to stable levels, e.g. 350ppm CO2 concentration in the atmosphere as has been the case for much of human existence, rather than a a 1.5°C or 2°C target, which is still well above the previously stable levels.

Tipping Points

The IPCC AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis explores the implications of abrupt changes and “tipping points”. The IPCC finds that the way that the Earth system is responding to warming is currently “proportionate to the rate of recent temperature change” but “some aspects may respond disproportionately”. In other words, there is an expectation that system responses to continued emissions and temperature rise may become increasingly non-linear.

A “tipping point” is defined as “a critical threshold beyond which a system reorganises, often abruptly and/or irreversibly”. Multiple tipping points may lead to a feedback mechanism that sees temperatures spiral, which is often referred to as ‘runaway climate change’.

The report finds evidence of abrupt change in Earth’s history and some “are associated with significant changes in the global climate”, such as “deglaciations” when an ice age came to an end. The report goes on to say, “such events changed the planetary climate for tens to hundreds of thousands of years....”

However, climate model projections for the next century currently do not show “non-linear responses… which indicate a near-linear dependence of global temperature on cumulative GHG emissions.” However, the summary for policymakers notes with high confidence that abrupt responses and tipping points in the climate system “cannot be ruled out”.

So the good news is the models do not show tipping points being triggered, however, that does not mean they cannot be.

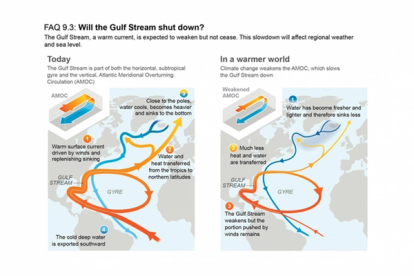

The report examines different potential tipping points, such as the shut down of the Gulf Steam, or thawing of permafrost which has the potential to release methane (a greenhouse gas which the IPCC AR6 states is 27-30 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 100 year time period).

FAQ 9.3: Will the Gulf Stream shut down?

Which scenario are we tracking?

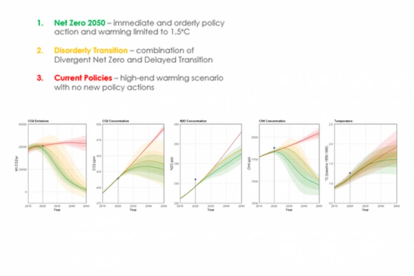

A key question for companies, investors, societies an

d all of us as individuals is which scenario are we presently tracking? To help our clients answer this question, the SLR climate team has developed a climate scenario tracking tool. The scenario tracking tool analyses real world data to see how we the world is currently tracking against three scenarios representing a low, medium and high-emissions trajectory.

Climate scenario tracking

The conclusion for 2021 is that the world is tracking a high-emissions scenario. The actions of global society over the next decade and beyond will influence the future direction of travel, since total CO2 emissions feed directly into the overall CO2 concentration in the atmosphere.

In the next post of this blog series, we will explore the highlights of the next IPCC report looking at the impacts of climate change on human society.

For support with climate change risk assessments, climate scenario analysis, developing your organisation’s climate strategy and capacity or responding to the TCFD reporting requirements please contact us.

Recent posts

-

-

Understanding sound flanking: Fire alarm speaker cable conduits in multi-family buildings

by Neil Vyas

View post -