Part one: Comminution, flotation and sample preparation at SLR’s mineral processing laboratory

by Ben Simpson

View post

Entering the second half of 2024, the first mandatory disclosures under New Zealand’s Climate-related disclosures (CRD) regime have been released, and of the estimated 200 climate reporting entities (CREs), approximately 20% have lodged their first climate statement.

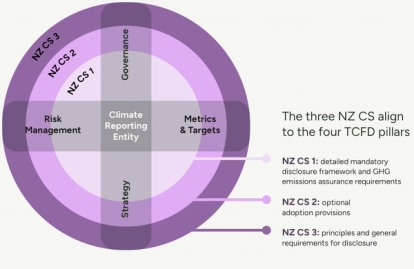

As a reminder, New Zealand’s climate-related disclosure framework is organised as a set of three interconnected standards (NZ CS), aligned to the pillars of the Task Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) recommendations (now under the IFRS S2 Climate-related Disclosures standard).

In following the Financial Markets Authority’s guidance that the first few years of disclosure will be broadly educational and constructive, most disclosures have focused on outlining their approach to climate-related risks and opportunities. Additionally, most CREs are also taking advantage of the adoption provisions available to them, particularly those related to current and future financial impacts. We are also noticing that most first-year disclosures are focused on direct operations, and we anticipate that future years will more explicitly align to the CRD’s value chain approach.

We’re seeing some patterns emerge under each pillar, and have noted key opportunities for next year’s reporting cycle (including for those who have yet to lodge their first statement):

Many disclosures are including a chart to visualise the respective roles of the board and management in addressing climate-related risks and opportunities. Some have dedicated sustainability/ESG committees and/or executives, while others have described how climate is incorporate into other roles. Most interestingly, keeping in line with the XRB’s guidance around transparency, several entities have described gaps in ensuring “appropriate skills and competencies are available to provide oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities.”

We would expect many of these gaps to be closed by the next reporting period as organisations continue to formalise their climate-related governance. In particular, we may see a shift from ad hoc training events focused on specific topics towards cohesive and comprehensive training programs.

It comes as no surprise that most companies have taken advantage of the first-year adoption provisions which allow for a one-year delay in the disclosure of current and future financial impacts as well as transition plan aspects of its strategy. However, we are seeing a thoughtful approach to scenario analysis, including ensuring alignment with the XRB’s specific instructions on analysing three scenarios. Companies are either using global, sector-agnostic scenarios such as those developed by the IPCC and IEA, or they are using scenario narratives which have been tailored for New Zealand and/or their sector (e.g., the New Zealand Banking Association Climate Scenario Narratives Report or the New Zealand Green Building Council’s Climate Scenarios for the Construction and Property Sector).

The next phase will require translating these analyses into more quantitative impacts and plans, especially as the adoption provisions under NZ CS 2 will no longer be available to entities. As it will be the first time disclosing this type of information, we may expect disclosures to be relatively coarse, but with supporting qualitative information on par with or even more detailed than this year.

Outside of governance, risk management is the most complete pillar that entities are reporting on. By and large, entities have reported that climate risk is incorporated into overall risk management frameworks, with only some value chain exclusions. Of additional note is that we are seeing large variations in the time horizons assessed (short-term can mean 1-10 years while the long term stretches from 10-100+ years!).

As entities continue to improve on other elements of their climate risk strategy, we may see that there are fewer parts of the value chain excluded.

Additionally, while not directly mandated by the Climate Standards, the variability in time horizons may begin to coalesce at a sectoral level to facilitate comparability for investors and regulators.

Most CREs are no stranger to reporting GHG emissions, and in addition to the Scope 1 & 2 disclosures required in the first year, some are also disclosing Scope 3 emissions. Additionally, a relatively high proportion of disclosures have assurance over some portion of their emissions, getting a head start on the requirement for FY 2024 lodgements. Beyond GHG emissions and some targets, there is a notable lack of disclosure for other required metrics, namely, the amount or percentage of assets or business activities vulnerable to physical/transition risks & opportunities.

We anticipate transition plan disclosures becoming more robust, particularly as current and anticipated climate impacts are quantified.

While this first year of reporting was a significant burden for reporting entities, we know that next year will be even more so. We’ll expect to see further attention on the quantification of impacts, transition planning, as well as more robust inclusion of the value chain. This also means we could see an uptick in reporting from large non-CREs, and smaller suppliers being asked questions by their large customers (and vice versa).

Get in touch if you want help preparing for the next phase of mandatory climate reporting.

We held a webinar covering some themes we’re seeing from recent disclosures as well as how climate-reporting entities and their value chains can set themselves up for success going forward.

For those that were unable to attend, you can view the recording at the link below.

View Webinar

by Ben Simpson

by Chynna Pickens, Claire Carter

by Vincenzo Giordano, Bob Robinson, Clément Barbaux