Car trip rates are falling in European cities thanks to vision-led planning — Will US cities follow?

- Post Date

- 05 February 2025

- Read Time

- 9 minutes

Foreword, by Ian Todreas, US Head of Sustainability Solutions

Across many US regions, states, and communities, cleaner air, reduced congestion, affordable housing, active lifestyles, vibrant places, and yes reduced CO2 emissions are converging objectives that feel overwhelming and nearly impossible to address. After all, we have spent decades aware of these issues, and yet, with population growth, inflation, larger cars, and urban sprawl, they seem to be more intractable than ever.

"Not so fast," points out my colleague, Paul Curtis, below. Based in the UK, Paul recently came to the US to join me at the Association for Commuter Transportation’s 2024 Transportation Demand Management Forum in Charlotte, NC, last November. There, we brought exemplary communities to our podium to share innovations in building the TDM city:

- Palm Beach County, Florida, is incorporating transportation demand management into all of its regulatory frameworks with the aim of reducing drive-alone rates;

- Austin, Texas, is taking advantage of multiple major transportation infrastructure projects to change travel behavior to increase transit, active modes, teleworking, and ridesharing; and

- Cleveland, Ohio, has reversed its zoning to encourage housing and development within 5-minute walk corridors of its rapid bus service.

These initiatives echo efforts of European cities that have pursued vision-led planning over time and have made demonstrable progress against the “nearly impossible.” Paul’s insights below explain how this happened and what it could mean for US cities—whether your city is ahead of or behind Palm Beach County, Austin, and Cleveland on its modal shift journey.

I have spent the last 16 years researching and working on international sustainable transportation projects and programs. And folks, something profound is afoot. During this period, I have studied and witnessed measurable trends across diverse countries in central and western European. Many towns and cities are adopting programs and measures that prioritize transit use, walking, cycling, and modern shared mobility modes instead of private car use. In short, in urban areas, prioritizing cars over people is no longer the norm.

This trend has been gradual, and yet so tangible, that it feels like a transportation variation of Darwin’s theory on evolution: for cities to survive (or in this case, improve livability), policymakers and residents need to adapt their approach to movement. In response to changes in the European urban ecosystem and through natural selection, transit, micro-mobility, and ride-hailing are beginning to thrive, while private car users are becoming a lesser dominant species.

What has changed?

Over the last 17 years, European cities have responded to a strong policy driver: the EU Air Quality Directive, which has set emissions ceilings for particulate matter pollution (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) to help meet international air quality guidelines. Cities and air quality districts can be – and have been – fined for breaching these limits.

Cities have also reacted to public pressure to address increases in asthma, other respiratory illnesses, and premature deaths caused by air pollution while promoting more physical activity and investing in walking and cycling infrastructure to tackle increasing obesity and reduce health care burdens.

Mayors also now seek to boost equity, employment access, and road safety through transportation investment. Economic growth is another factor influencing transportation shifts. Cities are aiming to accommodate projected population growth by redesigning streets to incorporate space-efficient options such as transit-priority corridors, sidewalks and dedicated bicycle lanes.

Higher capacity multi-modal street designs facilitate travel by commuters, shoppers, tourists, and students. And perhaps most obviously, many cities are leading the charge in climate action - where transportation emissions represent large portions of inventories that need reducing - in response to undeniable extreme weather events and international treaties.

What does the evolution look like?

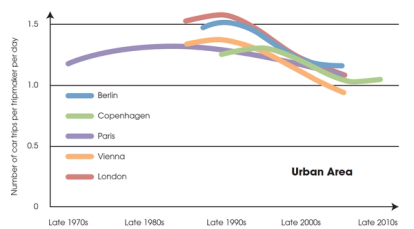

As part of the EU research project, ‘CREATE’, we investigated the changes in transport policy since the 1960s in five European capital cities: London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and Copenhagen. Three main stages in the evolutionary process emerged, each represented by the prevailing policies in those decades.

In the 1960s and 1970s, western European cities typically planned and designed for the car-oriented city. This car-centric design model resulted in increased road building, car parking capacity, and low-density developments.

In the 1980s and 1990s, these same cities saw greater investment in public transit and less emphasis on road building. They also imposed parking and access restrictions. The result was a move towards the sustainable mobility city which aimed to slow down the growth in car use for the first time via a combination of carrot and stick measures.

From 2000 onwards, our research showed that these carrots and sticks were deployed more strategically. European cities sped up investment in transit and bicycle infrastructure, micro-mobility, ride-sharing, transit-oriented development and integrated land use. In parallel, they also introduced street space reallocation, low emission zones restricting access for polluting vehicles and converted downtown car lots into public spaces and mixed-use developments. We call this phase the city of places.

Impact of the evolution

Plotting daily car trips across the decades reveals a fascinating but undeniable trend that underscores the impact of deploying a combination of carrots and sticks over time to prioritizing the movement of people above that of private cars. In short, during the 1960s and 1970s, in the capital cities studied, car use continued to increase before peaking in the 1980s and 1990s. Then from 2000 onwards, private car modal share dropped, with a shift to alternatives.

What happened in London?

London offers a particularly strong case study in this regard.

In 2003, the Congestion Charge was introduced, costing most car drivers $6.50 per day to enter central London. At the time, this limited traffic entering central London by 18 percent on weekdays. The fee has since increased to $18 and now applies to almost all vehicles

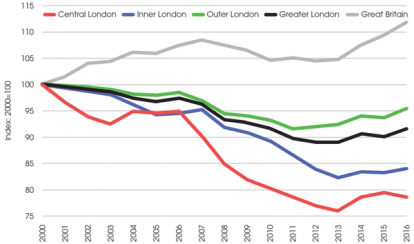

Between 2000 and 2016, Central London reduced its road capacity by approximately 30%, as shown in Figure 4. The city reallocated space from private vehicles to more space-efficient modes like cycling, walking, transit with further capacity provided in rail, light rail, and subway.

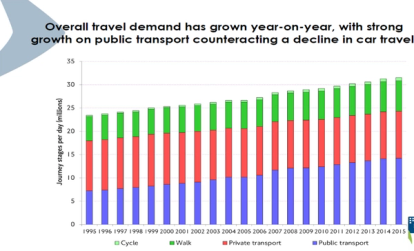

Meanwhile, during this period, London’s population increased from 7.2 million to 8.7 million, which in turn has generated a rise from 25 million to 31 million daily trips.

In short, the combination of transportation carrot and stick measures helped the city increase its capacity for mobility so that it could accommodate 6 million more daily trips. As seen in Figure 5, this was achieved by increasing cycle, walking and public transit trips, whilst reducing private transport (cars).

This increased population and total number of trips has led to economic growth and business investment. And despite less road capacity, the average car journey times today are broadly similar to 20 years ago, with an average speed of 7mph. This is a major achievement – despite being slower than a horse-drawn carriage in the 1900s.

These improvements have been the result of successive Mayors’ Transport Strategies. These have set mode share targets based around future visions for the city that prioritized good public health, air quality, physical activity, and road safety.

This powerful case study demonstrates that cities can achieve economic growth and higher livability standards through a vision-led approach to sustainable and more space-efficient mobility and land use.

Is this evolution already taking place in the US?

These trends have been replicated in many locales across Western Europe and beyond, but what about in the States? While further research is needed, my sense is that an evolution is underway in many urban areas.

In January 2025, New York became the first US city to introduce a congestion charge scheme, costing $9 for most vehicles to enter the designated zone at peak hours. The city has also invested in cycling infrastructure and bike sharing, which has contributed to the 64 percent increase in ridership between 2013 and 2023. Carrots and sticks in action!

As Ian mentions above, last November, at the 2024 Association of Commuter Transportation TDM Forum in Charlotte, NC, I joined more than 150 transportation demand management professionals, who are working to elevate the movement of people above cars and are delivering truly impressive sustainable transportation policies and programs across the United States. But realistically, they face tremendous headwinds. Decades, if not centuries, of development have evolved around expansive landscapes and divergent, often unplanned land uses. And today federal support for climate action is waning.

Yet, American urban leaders and dwellers alike want economic growth, attractive and vibrant downtowns, clean air, accessibility, and 21st century mobility choices. These desires are highlighting the benefits of people-first mobility and “driving” car-favored policies and programs off the road. Let’s hope it doesn’t take 16 more years to see car trips start to drop. Given American ingenuity and its optimistic can-do spirit, it shouldn’t.

Want to accelerate your municipality or development’s mobility evolution? Contact us. With our international expertise and local presence across the United States, the SLR Consulting team is ready to help you on your journey.

SLR Consulting is an international firm helping public and private sector clients achieve their sustainability goals. We specialize in working at the intersection of climate and transportation, providing planning, engineering, decarbonization, and resilience services. Let us help you in Making Sustainability Happen. Contact Ian Todreas at itodreas@slrconsulting.com for more information.

Recent posts

-

-

Navigating the evolving landscape of corporate sustainability and communications in the US

by Chynna Pickens

View post -