Reducing energy costs while driving decarbonisation in the food & beverage industry

by Vincenzo Giordano, Bob Robinson, Clément Barbaux

View post

The potential introduction of a Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) for recyclable drinks containers in the UK draws a variety of opinions on the respective merits of such systems, and the drivers behind their implementation.

This article provides an overview of the introduction of one scheme in the Australian State of New South Wales (NSW), just one of the global regions in which SLR has recently provided technical support on development and implementation of strategic approaches to solid waste management, and concludes by discussing factors for consideration in configuring a UK DRS system.

The NSW System

NSW introduced the ‘Return and Earn’ container deposit scheme (CDS) in December 2017, placing a 10 cent deposit on eligible drink containers which can be redeemed at any of the 650+ approved collection points that have been introduced across the State. Eligible containers include those most commonly used away from the home and found in the NSW litter stream (most glass, cans, plastic and paperboard drink containers between 150ml and three litres).

The primary driver behind the scheme was litter reduction. Drinks containers were thought to represent as much as 44% of litter generation, costing the State an estimated $162M to clean up each year. The scheme was identified as a key mechanism to achieve the State target of reducing litter by 40% by 2020[1].

How Does the Return and Earn Scheme Work?

A network of collection points continues to be developed across the State by the ‘Network Operator’ (TOMRA Cleanaway), prioritising collection areas in metropolitan and regional locations through a combination of:

· Reverse vending machines (RVMs);

· Automated depots (for bulk returns);

· Over the counter sites (for small quantities, generally via local shops); and

· Donation stations (self-service RVMs for donations only, with no refunds given).

Local schools, charities, sports teams and community groups can benefit from the scheme, as in some cases those returning containers are able to choose between taking the refund themselves or donating the value to registered organisations in their area.

To fund the scheme, manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers and retailers are all required to register as ‘suppliers’ and pay a monthly fee which reflects their market share.

The fee structure is designed to include the ten cent return value plus the costs of administering and managing the scheme. The total estimated range of fees for the first three months after the scheme’s introduction (exclusive of GST) was:

· 10.94 to 13.54 cent for aluminium containers;

· 11.36 to 14.07 cent for glass containers; and

· 11.13 to 13.78 cent for PET containers[2].

Management of the system is the remit of the ‘Scheme Co-Ordinator’ (Exchange for Change) – which provides financial management and community education support.

Although the scheme was introduced primarily to reduce litter, eligible containers collected at the kerbside and delivered to material recycling facilities (MRFs), through NSW’s predominantly commingled recyclables collections services, are also included in the system. As a result, one likely outcome is an impact on both the composition and quantity of recyclables collected at the kerbside. Container Deposit Schemes of this type have the potential to reduce quantities of higher value materials collected through household waste services (e.g. aluminium cans and PET plastic bottles) resulting in reduced revenues for MRFs, which may in turn result in them increasing their gate fees for processing mixed recyclables.

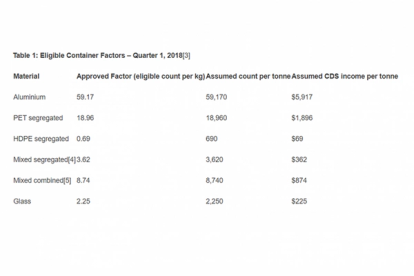

In NSW, MRF operators are entitled to receive quarterly ‘processing refunds’ for eligible containers which pass through their facility, including material received via local government kerbside collections. Using the results of audits conducted on MRF outputs, the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) calculates an ‘Eligible Container Factor’ for each kilogramme of different materials processed, examples of which are shown in Table 1 below for Q1 2018.

MRF operators may use this factor to calculate the refund they can claim (based on the weight of eligible material processed) or alternatively can count each eligible container.

Research commissioned by NSW Government into the potential economic impacts of the scheme on MRF operators[6] estimated that additional revenues arising from eligible containers collected through kerbside recycling systems could be worth around $100 million per annum for councils and MRF operators across NSW. The number of eligible containers in each tonne of commingled MRF input material was estimated to be at least 1,500 to 2,000, suggesting that the level of refund available would be between $150 and $200 per input tonne.

The same research concluded that the direct cost of CDS compliance on NSW MRFs is very low (at around 5% of estimated additional revenue) and that eligible containers are worth more from the CDS refunds than their current value in commodity markets.

A key consideration in a wider context is the extent to which a reduction in total tonnage of materials collected at the kerbside, as a result of residents claiming refund values themselves, offsets the additional MRF income derived from CDS refunds.

To be able to claim the eligible refunds specific to council kerbside collections, suitable agreements must be in place between the collecting council and their MRF contractors to define how CDS income will be returned to the supplying council, and how this process will be monitored. Approved mechanisms include:

MRF operators must also provide evidence that the containers for which they are claiming the refund have been recycled appropriately, including submission of monthly data, quarterly claims and an annual recycling report which must all be presented in a prescribed format.

Failure to have an appropriate agreement in place or provide suitable evidence of recycling can result in both the council and MRF operator being ineligible to receive applicable refund payments.

A generic summary of material and money flows created by a DRS is shown in Figure 1 below.[7]

Figure 1: Typical Material and Money Flows in a DRS

Has Return and Earn Worked?

As the scheme nears completion of its first year, some early outcomes can be identified and conclusions drawn as to its effectiveness.

Inevitably, the overall cost of the scheme to manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers has been passed on to consumers through an uplift in product costs. Anecdotally the level of cost increases being applied has in some cases exceeded the costs associated with the scheme. With higher costs being introduced almost immediately following the introduction of the scheme, there has been some initial criticism associated with residents not being able to offset higher shopping bills by recouping the refund value locally. This has been due to the programmed roll out of collection points not providing sufficiently accessible outlets (particularly in more rural areas) in the early months of implementation[8].

However, in terms of the capture of materials the scheme appears to have been successful, with Exchange for Change indicating that in the first four months almost 200 million containers were recycled that would otherwise have ended up in landfill or in the litter stream. This was accompanied by a rise in the kerbside recycling rate for beverage containers from 33% to 61%.[9] At the time of writing, the Return and Earn website claims that over 700 million eligible containers have been returned, equating to approximately 3 million containers being returned each day.

In August 2018, Keep Australia Beautiful reported a 33% drop in Return and Earn eligible drink containers in the litter stream since November 2017, immediately prior to the scheme’s introduction[10], although in SLR’s experience of working in Australia and NSW specifically, collation of robust litter data is often cited as an area for improvement.

Lessons Learned for Application in the UK?

Whilst there is currently no definitive information on precisely how a DRS scheme might be applied to achieve the most successful outcomes in the UK context, it seems highly likely that a scheme will be introduced at some point in the near future[11]. Of course this is not a ‘new’ approach in the UK, where deposit returns for glass bottles were commonplace into the 1980s prior to the explosion in the use of cheaper plastic alternatives.

Some opposition to the concept has already been expressed, notably from the aluminium recycling sector which believes that a DRS is not necessary for aluminium as high recycling rates are already being achieved.[12]

Lessons learned from the NSW experience, and wider implications for the UK include:

1. Appropriate Level of Refund – the value should be set at a suitable level to influence behavioural change.

2. Achievable Roll Out Programme - sufficient time should be allowed to set up collection points which are accessible for all.

3. Effective Location Management – return points should be available, easy to use and well maintained.

4. Allocation of Scheme Costs – linkages between a DRS and complementary Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) measures must be fully considered so the overall system is seen as ‘fair’ whilst driving positive changes in both manufacturer and consumer behaviour.

5. Use of Funds – directing some refund values towards supporting local community organisations and projects would generate positive publicity.

6. Impact on MRF Operators – the operational and economic impact on the UK MRF sector must be robustly assessed.

7. Impact on Local Authorities – the effects of changes to kerbside collection systems and all other associated costs (e.g. litter management) should be considered.

8. Scope of Container Eligibility – limiting the scope of a UK DRS to ‘on the go’ containers consumed outside of the home, could mitigate potential loss of income to local authorities through reduced kerbside collection tonnages.

9. Scope of Materials – focussing on specific materials (e.g. certain types of plastic) could promote development of associated reprocessing infrastructure in the UK.

10. Quality Requirements – returned containers should be in a suitable condition for recycling.

The overall financial impacts and linkages with potential wider change in waste management practices will need to be fully considered for maximum benefits to be realised.

For example, if the UK were to move to a ‘pay as you throw’ system then intuitively a DRS which includes kerbside collections could result in reduced income for councils from the sale of recyclable materials collected, although this could be partially offset by reduced litter management costs. Householders could potentially benefit through reduced bills for collection services and increased income from container deposits.

Recent indications from UK Government are that the ‘imminent’ publication of the eagerly anticipated Resources and Waste Strategy will shed further light on a range of key issues within the resources and waste management sector, including consideration of fiscal measures which will be deployed to support the achievement of Defra’s objectives.[13]

It is open to question whether the primary motivation behind a DRS in the UK should be to reduce litter, drive changes in manufacturing processes, produce higher quality recyclable materials, influence consumer buying habits or any combination of the above.

Clearly a DRS is not the answer to all of the UK’s environmental concerns, but it may have a role to play as part of a package of measures aimed at stimulating change. The structure of the package and the interactions between each of its components will ultimately dictate the overall impacts and success of the wider UK strategy.

For further information on this please contact the author Grant Pearson, Principal - Waste & Resource Management (Shrewsbury) - gpearson@slrconsulting.com.

[1] https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/your-environment/recycling-and-reuse/return-and-earn

[2] http://www.exchangeforchange.c...

[3] https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/you...

[4] For MRFs which segregate PET and HDPE plastic types, this category refers to the remaining plastic types, in aggregate.

[5] This category applies to MRFs which do not segregate plastic types, and refers to all plastic types, aggregated.

[6] Container Deposit Scheme.

[7] Source: Envision (2015) The Incentive to Recycle: the case for a container deposit system in New Zealand

[8] http://www.abc.net.au/news/201...

[9] https://returnandearn.org.au/e...

[10] http://wastemanagementreview.c...

[11] https://www.letsrecycle.com/ne...